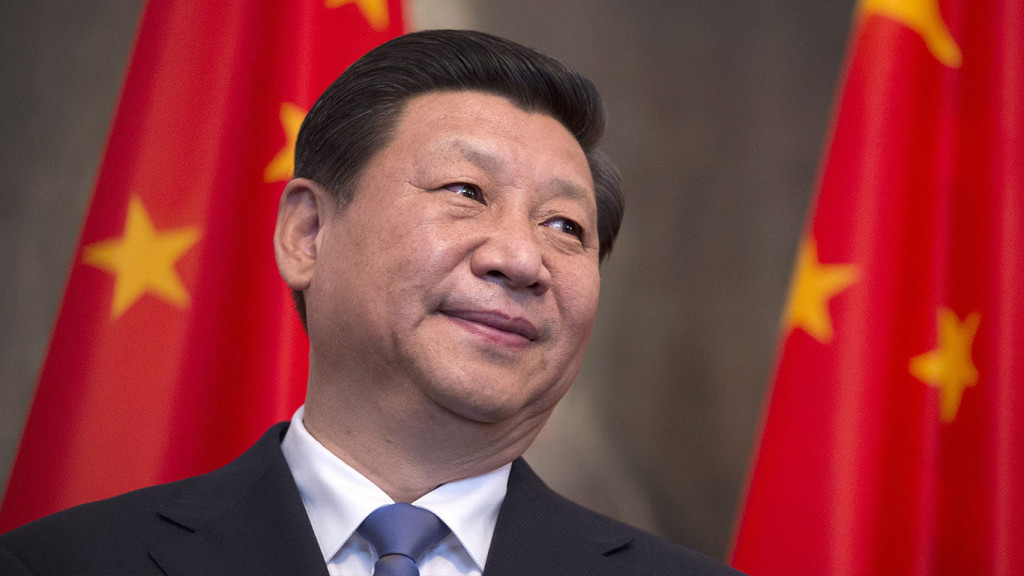

Let’s talk about China’s belt and road. This initiative has seen China financing and providing loans for development and infrastructure projects mostly in the global south. Western media will have you believe that China is “dept trapping” these countries. Dept trapping is a technique where Western countries and financial institutions will offer development loans to countries in the global south. The interest rates on these loans are made incredibly high trapping these countries in severe debt giving western countries and business interests incredible control over their 21`3w3economic and political systems. The existence of the IMF and World Bank which were created during world war 2 also allows the U.S to control who gets global financing. After socialist Salvador Allende was democratically elected in Chile Richard Nixon said “make the economy scream” and the IMF cut Chile’s financing from 200 million to 2 million. Compare this to the loans and financing that the U.S offers to its allies in Europe. After world war 2 to help rebuild European infrastructure they went through with the Marshall plan providing European countries with long-term loans at about a 2% interest rate. This allows the U.S to build up its geopolitical allies in Europe while also building up the global financial system itself. A global system built to maximize exploitation in the global south for the benefit of greedy capitalists in the west. Much of what China is doing with the belt and road a counter to the U.S controlled financial system offering loans to countries mostly in the global south at similar interest to the marshall plan. I think a lot of fear surrounding the belt and road is an American projection and assuming that China will treat these countries the same way as the west. So China is pedaling for influence but it’s nowhere near western imperialist debt trapping Western media makes it out to be. Xi’s vision included creating a vast network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, and streamlined border crossings, both westward—through the mountainous former Soviet republics—and southward, to Pakistan, India, and the rest of Southeast Asia. Such a network would expand the international use of Chinese currency, the renminbi, and “break the bottleneck in Asian connectivity,” according to Xi. (The Asian Development Bank estimated that the region faces a yearly infrastructure financing shortfall of nearly $800 billion.) In addition to physical infrastructure, China plans to build fifty special economic zones, modeled after the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, which China launched in 1980 during its economic reforms under leader Deng Xiaoping.

Xi subsequently announced plans for the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road at the 2013 summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Indonesia. To accommodate expanding maritime trade traffic, China would invest in port development along the Indian Ocean, from Southeast Asia all the way to East Africa and parts of Europe. China’s overall ambition for the BRI is staggering. To date, more than sixty countries—accounting for two-thirds of the world’s population—have signed on to projects or indicated an interest in doing so. Analysts estimate the largest so far to be the estimated $60 billion* China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a collection of projects connecting China to Pakistan’s Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea. In total, China has already spent an estimated $200 billion on such efforts. Morgan Stanley has predicted China’s overall expenses over the life of the BRI could reach $1.2–1.3 trillion by 2027, though estimates on total investments vary. So What does China hope to achieve? China has both geopolitical and economic motivations behind the initiative. Xi has promoted a vision of a more assertive China while slowing growth and rocky trade relations with the United States have pressured the country’s leadership to open new markets for its goods. Experts see the BRI as one of the main planks of bolder Chinese statecraft under Xi, alongside the Made in China 2025 economic development strategy. For Xi, the BRI serves as pushback against the much-touted U.S. “pivot to Asia,” as well as a way for China to develop new investment opportunities, cultivate export markets, and boost Chinese incomes and domestic consumption. “Under Xi, China now actively seeks to shape international norms and institutions and forcefully asserts its presence on the global stage,” writes CFR’s Elizabeth C. Economy. At the same time, China is motivated to boost global economic links to its western regions, which historically have been neglected. Promoting economic development in the western province of Xinjiang, where separatist violence has been on the upswing, is a major priority, as is securing long-term energy supplies from Central Asia and the Middle East, especially via routes the U.S. military cannot disrupt. More broadly, Chinese leaders are determined to restructure the economy to avoid the so-called middle-income trap. In this scenario, which has plagued close to 90 percent of middle-income countries since 1960, wages go up and quality of life improves as low-skilled manufacturing rises, but countries struggle to then shift to producing higher-value goods and services.

What are the potential roadblocks for China in the future? The Belt and Road Initiative has also stoked opposition. For some countries that take on large amounts of debt to fund infrastructure upgrades, BRI money is seen as a potential poisoned chalice. BRI projects are built using low-interest loans as opposed to aid grants. Some BRI investments have involved opaque bidding processes and required the use of Chinese firms. As a result, contractors have inflated costs, leading to canceled projects and political backlash. Examples of such criticisms abound. In Malaysia, Mahathir bin Mohamad, elected prime minister in 2018, campaigned against overpriced BRI initiatives, which he claimed were partially redirected to funds controlled by his predecessor. Once in office, he canceled $22 billion worth of BRI projects, although he later announced his “full support” for the initiative in 2019. In Kazakhstan, mass protests against the construction of Chinese factories swept the country in 2019, driven by concerns about costs as well as anger over the Chinese government’s treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang Province.

More such stories are likely, according to a 2018 report by the Center for Global Development, which notes that eight BRI countries are vulnerable to debt crises. CFR’s Belt and Road Tracker shows an overall debt to China has soared since 2013, surpassing 20 percent of GDP in some countries. The United States views India as a counterweight to a China-dominated Asia and has sought to knit together its strategic relationships in the region via the 2017 Indo-Pacific Strategy. Yet, despite U.S. misgivings, India was a founding member of China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and Indian and Chinese leaders have invested in developing closer diplomatic ties. “India does a lot with China in the multilateral arena for its own reasons,” says CFR’s Alyssa Ayres.

Japan. Tokyo has a similar strategy, balancing its interest in regional infrastructure development with long-standing suspicions about China. In 2016, Japan committed to spending $110 billion on infrastructure projects throughout Asia. Japan has, with India, also agreed to develop the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC), a plan to develop and connect ports from Myanmar to East Africa. Europe. Several countries in Central and Eastern Europe have accepted BRI financing, and Western European states such as Italy, Luxembourg, and Portugal have signed provisional agreements to cooperate on BRI projects. Their leaders frame cooperation as a way to invite Chinese investment and potentially improve the quality of competitive construction bids from European and U.S. firms. Others disagree. French President Emmanuel Macron has urged prudence, suggesting during a 2018 trip to China that the BRI could make partner countries “vassal states.” Other skeptics connect the BRI with climate change. The Institute of International Finance, a research group that analyzes risk for large Western banks, has reported that 85 percent of BRI projects can be linked to high levels of greenhouse gas emissions. Others claim that China is using BRI funds to gain influence in Balkan countries that are on track to become EU members, thereby providing Chinese access to the heart of the European Union’s common market.

Russia. Moscow has become one of the BRI’s most enthusiastic partners, though it responded to Xi’s announcement at first with reticence, worried that Beijing’s plans would outshine Moscow’s vision for a “Eurasian Economic Union” and impinge on its traditional sphere of influence. As Russia’s relationship with the West has deteriorated, however, President Vladimir Putin has pledged to link his Eurasian vision with the BRI. Some experts are skeptical of such an alliance, which they argue would be economically asymmetrical. Russia’s economy and its total trade volume are both roughly one-eighth the size of China’s—a gulf that the BRI could widen in the coming years.

By: Kyle Barrett